Each blade is ground to an angle of 25º using a Tormek low-speed wet grinder to avoid any chance of burning the edge.

The bevel is honed using diamond paste on a cast iron plate. Sometimes an intermediate abrasive (usually 3 micron diamond paste) is used at about 2º less than the final angle, and then the final diamond abrasive is used on a different cast iron plate.

All of the blades are sharpened with a back bevel of 2½ º. The results are recorded as if the plane had a bed angle equivalent to its true bed angle plus the angle of the back bevel. So far all of the planing has been done using planes with 45º beds.

In the years since I wrote these pages my sharpening jig has evolved. The current version can be seen here.

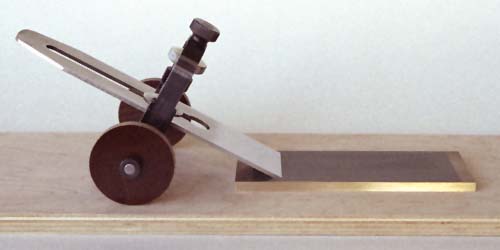

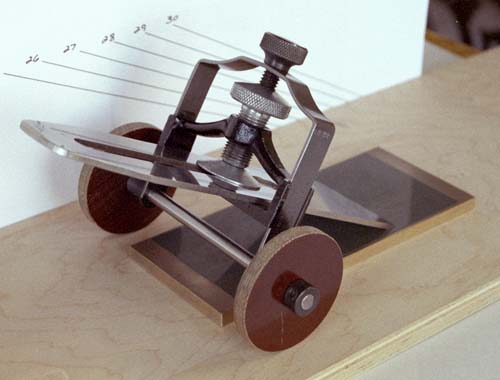

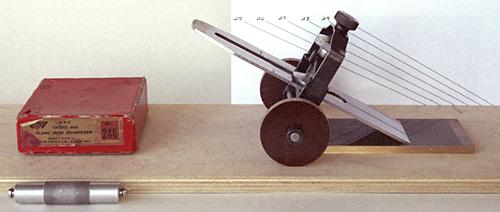

To make sure the bevel angle is precise I use a modified Millers Falls #240 honing jig. The modification I’ve made is to remove the roller and replace it with an axle and wheels that don’t ride on the stone. This allows me to make strokes along the entire length of the stone. Here are some pictures of my first version of this modification:

The black knob on the top of the jig adjusts the bevel angle within a range of about nine degrees, depending on blade extension. Since I took these pictures I’ve done an extensive new version of this setup. It now includes a holder for stones that rocks back and forth so that the blade edge always touches the stone across the blade’s entire width. This makes setting the jig much quicker.

The new version also includes a provision for honing back bevels. It allows me to alternate between honing the main bevel and the back of the blade, which is how I’ve had the most success in removing all of the wire edge. For pictures of the new version, click here.

After considerable experience honing and examining blades of different types, I’ve become convinced that a more finely honed edge is usually achieved through use of a back bevel. I’ve been a professional cabinetmaker for 25 years and had never used back bevels until I started this study, preferring to lap the entire back of the cutting portion of the blade. After examining and testing many blades that I thought would be sharp and finding scratches or a wire edge, I now prefer a carefully honed, very narrow back bevel. This is especially important for the more wear-resistant alloys.

I’m experimenting with different abrasives for final honing: waterstones, diamond paste, oilstones, and fine abrasive papers. It has become clear to me that different types of steel require different honing abrasives. For more information, see the page Abrasive Choice.

A more complete description of the the appearance of the surfaces produced on steel by different abrasives can be found on the page Surfaces on Steel.

For a few tips on using the different methods of sharpening, see Tips on Sharpening.

I’m experimenting with a device that uses a laser pointer to precisely measuring the honed bevels on a blade. Here’s an image showing a freshly honed Hock high carbon blade: